I first learned the word arbitrage in an upper-level economics class.

It was introduced plainly enough, almost offhandedly, as a mechanism of markets. If an investment offers unusually high returns, people will notice. Capital flows in. Prices rise. Returns fall. Over time, the advantage disappears. The system settles back into a more even state.

There was no drama in the definition — just a quiet implication: exceptional conditions invite pressure, and pressure tends to normalize things.

What struck me wasn’t the word itself, but how immediately it escaped the classroom.

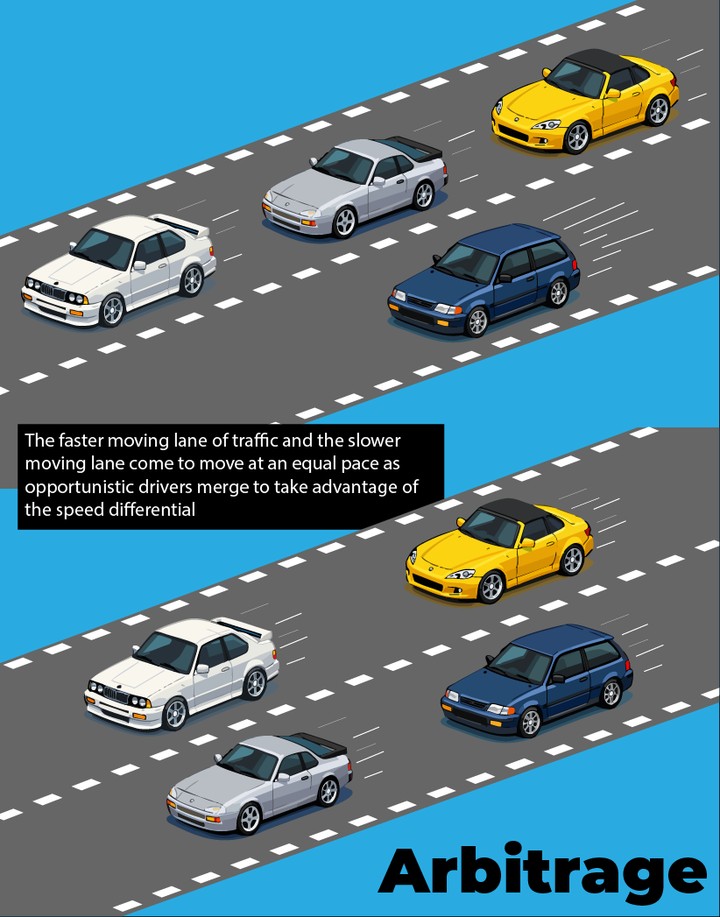

Driving home that afternoon, I noticed a lane on the freeway moving faster than the others. Cars began to drift toward it — not all at once, but steadily. The faster lane slowed. The slower lanes sped up. Before long, every lane was moving at roughly the same pace again.

That was arbitrage.

Once you see it, you start seeing it everywhere.

Arbitrage in Markets

In finance and commodities, arbitrage is easiest to explain.

If two identical assets are priced differently, traders buy the cheaper one and sell the more expensive one. Their actions eliminate the difference. The opportunity disappears precisely because it was exploited.

In a well-functioning market:

-

Unusually high returns attract attention

-

Attention attracts capital

-

Capital compresses returns

The result is not equality of outcomes, but equality of opportunity. Persistent advantage is rare, not because it’s forbidden, but because it’s unstable.

Arbitrage is the force that enforces that instability.

Arbitrage on the Freeway

Traffic behaves the same way.

A faster lane represents excess return — less time, less friction, less cost. Drivers respond rationally. They move toward it. The lane fills. Its speed drops. Meanwhile, the lanes they left behind thin out and speed up.

No central authority equalizes traffic flow. It emerges from individual decisions reacting to local information.

What matters here is not that drivers seek fairness, but that they seek advantage. The fairness is a byproduct.

Arbitrage in Physics: Entropy Under Constraints

The same pattern appears even where there are no drivers, traders, or decisions.

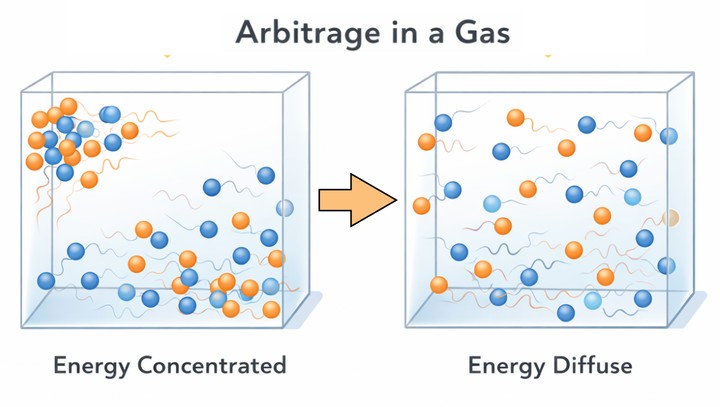

Consider a box of gas particles. Each particle moves randomly, colliding, bouncing, changing direction. Over time, the gas spreads evenly throughout the container. This is often described as entropy maximization under constraints.

Brownian motion — the jittery, random movement of particles suspended in fluid — is a visible example. Individual particles move unpredictably, but the system as a whole trends toward uniformity.

Where particle density is higher, pressure is higher. Particles diffuse away from those regions. Differences get smoothed out, not because the system “wants” fairness, but because imbalances create gradients, and gradients drive flow.

That diffusion is arbitrage without intent.

A General Pattern

Across traffic, markets, and physics, the structure is the same:

-

A difference appears

-

The difference creates incentive or pressure

-

Movement occurs in response

-

The difference shrinks

Arbitrage isn’t about optimization or morality. It’s about systems responding to gradients — of price, time, energy, or probability.

The lesson I carried with me from that class wasn’t how to exploit arbitrage, but how rarely it lasts. Advantage is temporary. As soon as it becomes visible, it becomes crowded.

And that realization — that equilibrium is not imposed, but emerges — has stayed with me far longer than the definition ever did.

Teleology, or the Invisible Hand?

Arbitrage can be mistaken for a kind of purpose or intention, as though systems are trying to reach balance. This is a teleological illusion. Nothing in a market, a freeway, or a gas “wants” equilibrium in the way a person wants an outcome. What we observe instead is the cumulative effect of local responses to local conditions. Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” points at the same misunderstanding from the opposite direction: order appears intentional only because the process that produces it is distributed. Arbitrage has no goal, no end state it seeks to achieve. It is simply the name we give to the way gradients create motion, and motion erodes gradients. The appearance of purpose emerges only when we step back and view the system as a whole.

This is a remarkable truth, it's a phenomenon that appears everywhere, and by accepting it we can live more rational, intentional, and pragmatic lives. It encourages patience. It encourages the stalwart & steadfast pursuit of one's goals.